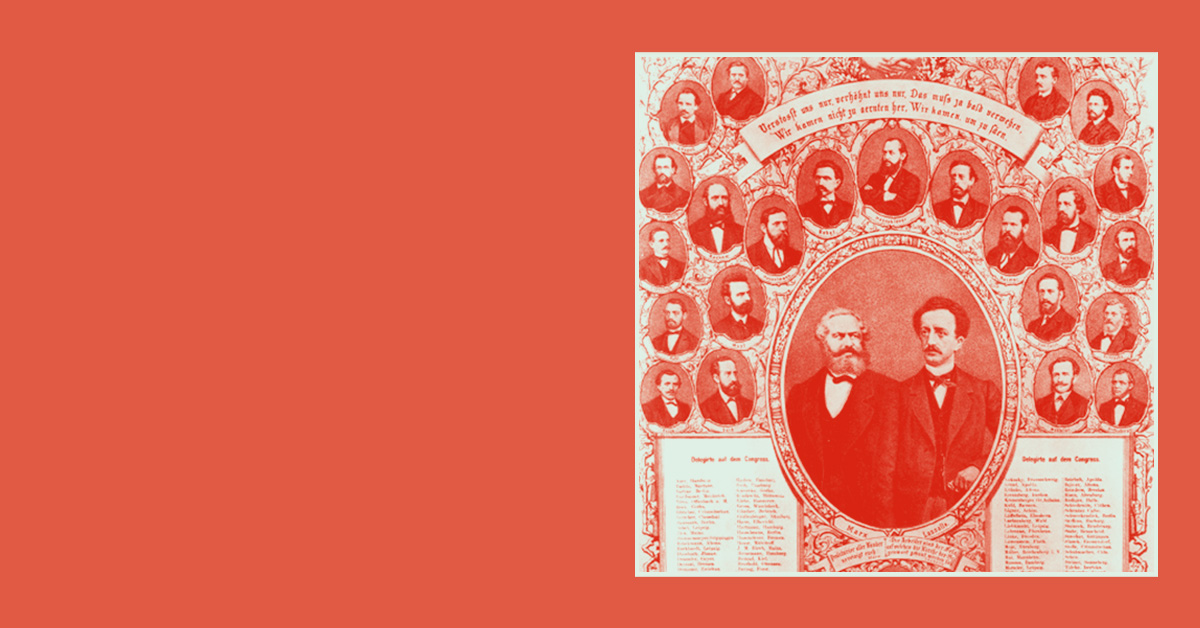

Just over 150 years ago, two workers’ parties united under a programme declaring that “The liberation of work must be the work of the working class”. This liberation consisted of a socialist society and the abolition of the system of wage labour. It declared itself to be in favour of an unrestricted right of association, universal equal suffrage, and a people’s militia instead of a standing army. Together, this single party now represented over 25,000 workers, all of whom were proud to call themselves Social Democrats. This party, founded at Gotha over five days in May 1875, would go on to become the largest Marxist party in the world, boasting a million members by 1914. In the half-century after its founding, it would serve as a model and inspiration for socialists from places as varied as the Balkans, Japan, and Iran.

However, its founding programme, that it maintained up until 1891, is rarely celebrated, much less read. Karl Marx’s critical marginalia on a draft version – now immortalised as the Critique of the Gotha Programme – have, it seems, settled the matter for socialists. The Gotha Programme was a hopelessly backwards step; a triumph of Ferdinand Lassalle’s errors over Marx’s understanding of capitalism, dooming Social Democracy from its birth. It has been blamed, at various times, for Social Democracy’s statism, its nationalism, its compromises, and the enduring influence of Lassalle himself who epitomises all these failings. Far from being the one of the first steps to building a coherent socialist working-class party, the Gotha Programme is treated as the movement’s original sin.

But the Gotha Programme was a success, and it was a success despite the pessimistic expectations of Marx and Engels, who watched from afar in London. In October 1875, Engels wrote to Bebel that the whole affair was an “educational experiment” and “unification as such will be a great success if it lasts two years”. It is the same Engels who published Marx’s notes on the programme in Die Neue Zeit in 1891. In his own words, after fifteen years, “Lassalleans only continue to exist in isolated ruins abroad.” He redacted some of Marx’s insults, as he claimed Marx himself would have done.

Put simply, the Critique of the Gotha Programme is world famous precisely because Marx and Engels were wrong about the organisation’s prospects: the programme proved to unify the disparate, often floundering parts, into a noble, even heroic organisation that could withstand over a decade of fierce political persecution without disintegrating. The programme did, of course, need revision to respond to Bismarck’s Anti-Socialist Laws, which outlawed most of the party’s structures at a stroke. In 1880, two years after the laws were passed, a group of German socialists met covertly in the thirteenth-century Wyden Castle, near Zurich. They voted to strike out one word from their programme – the word “legal” from the sentence “the party strives for its goals through all legal means.”

What was the workers’ movement like in Germany, and how did it unify? Our story starts in May 1863, with the founding of the General German Workers’ Association (Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiter-Verein, ADAV). It does not begin with Ferdinand Lassalle. It starts with a committee of workers, a mix of veterans of the 1848 revolution and those who acquired political consciousness in the workers’ educational associations presided over by affluent liberals. In April 1862, Julius Vahlteich, a shoemaker, and Friedrich Fritzsche, the founder of the German tobacco workers’ union, attempted to make their Leipzig educational association into a political group, in a motion put forward in an extraordinary assembly. It was rejected; among the opponents was a young August Bebel. Vahlteich and Fritzsche, alongside the chemist Dr Otto Dammer, wrote to Lassalle in December 1862, asking for guidance in achieving a political workers’ movement. Rosa Luxemburg describes them in these terms: “the Leipzig elite of the German proletariat, who already sought to free themselves from the tutelage of the liberal bourgeoisie, and were groping for the right path.”

Ferdinand Lassalle wrote an open letter back. He outlined an economic theory, now derided by Marxists as the “Iron Law of Wages” – that wages on average will always tend to the minimum required for existence. Trade union struggle is hence fruitless. The only way that workers could be liberated from such a law is through setting up their own productive associations, with the capital provided by the state. And in order to secure the help of the state, workers had to organise themselves into a political force. And so Lassalle stated unambiguously: “The working-class must constitute itself an independent political party, based on universal equal suffrage: a sentiment to be inscribed on its banners, and forming the central principle of its action.”

It’s a persuasive argument. On 23 May 1863, in Leipzig, the Allgemeiner Deutschen Arbeitervereins (ADAV) was founded, with eleven delegates, five honorary guests, and some hundred Leipzig workers. Lassalle was elected president, and Vahlteich secretary. They adopted Lassalle’s open letter as the programme. It was an organisation that could not exist nor survive without the initiative of politically conscious workers, already seeking to organise themselves. They were the making of Lassalle.

These developments didn’t go unnoticed by the liberal bourgeoisie. On 7 June, the Verband der Deutscher Arbeitervereine was founded, in which delegates representing 54 workers’ educational associations from 48 cities gather in Frankfurt am Main. Among them was August Bebel. Its key resolution was directed against Lassalle’s organisation, even if he goes unnamed, as disrupting the unity of all those striving for the betterment of the working class. In Bebel’s recollections, following the foundation of the ADAV, the workers’ movement witnessed scenes that “make a mockery of any attempts to describe them”, including violent brawls.

Almost from the moment ADAV was founded, it was the site of internal struggles – about the unlimited power of Lassalle as president of the organisation, his suspected alliances with Bismarck, then seeking to unify Germany by the Prussian sword, and the attitude towards trade unions. Julius Vahlteich resigned from his position on the executive in January 1864. When he wrote about his time in the ADAV in 1880, he recalled “Lassalle… was the association; he financed it with his money, he led it according to his will and he spoke for it with his writings. The executive of the association was muzzled.” On 21 May 1864, the Berlin section of the ADAV celebrated the ADAV’s anniversary by paying tribute to Wilhelm Liebknecht, and Karl Marx as the founders and pioneers of the party of the proletariat. This is despite Liebknecht having only joined the organisation in the autumn of 1863. Friedrich Fritzsche, while remaining a prominent figure in the ADAV up until Lassalle’s death, organised cigar workers, founding the German Cigar Workers’ Union in 1865 – the first national union – and sought to bring his political and industrial work together. The ADAV did not rally around “Lassalleanism” as Marxists today think they did.

Lassalle did not take the rising opposition lying down, of course. Together with the ADAV vice-president Otto Dammer, he pushed for the expansion of his power as president against the executive, and appointed his allies as new executive members. We do not know how the power struggle might have unfolded. On 31 August, Lassalle lost his life in a duel for the love of a Protestant aristocrat. At the time of his death, the ADAV had roughly 4,600 members. His agitational success, his desire to leapfrog the slow work of history through daredevil will, and his commitment to the working class are why Rosa Luxemburg praised him as head and shoulders above the enlightened “petty-minded peddlers of historical research” who emphasised his mistakes. Over half of these were in the Rhineland, where Christian workers’ associations were also flourishing.

Leadership of the ADAV was eventually passed onto Johann Baptist von Schweitzer, who edited the paper Der Social-Demokrat – the funding of which was never made particularly clear. For a few months immediately after Lassalle’s death, Marx and Engels themselves were involved in negotiations about taking over the leadership of the ADAV, however, Marx refused, suspecting that Schweitzer adhered to Lassalle’s strategy of allying with the Prussian government. Schweitzer was a man of many talents; Bebel recalled him as “a demagogue of the grandest style”. He was also a man determined to enforce his own will upon the party, expelling the opposition, tarnishing critical voices as spies or intelligence operatives, and suppressing all views but his own in Der Social-Demokrat. Wilhelm Liebknecht himself was expelled from the ADAV in 1865. The party grew, but it was organisationally ramshackle.

The Beginnings of the Eisenachers

This brings us to the people who would become the Eisenachers – initially known, and lampooned, as the Ehrlichen (‘the honest ones’). Wilhelm Liebknecht was a veteran of the 1848 Revolution, who fled the German courts after crowds demanded his release, and relocated to London in 1850. In his exile, he was “almost daily and for years nearly all day in the house of Marx” and subjected to a rigorous regimen of self-criticism. He returned to Germany in 1862 after an amnesty for 1848 revolutionaries was declared, and set to work – constantly corresponding with Marx about events on the ground.

August Bebel grew up in poverty in Wetzlar, after his father died of tuberculosis. Ever the contrarian, he was one of two school students who spoke up for the monarchy: in recompense their republican peers beat them up. He took up employment as a turner, and, while he toured Austria to learn the trade, he joined a Catholic workingmen’s association. He remembered it as his first encounter with political ideas, through reading the newspapers. When he arrived in Leipzig in 1860, he was interested in workers’ organisations, but as he recalled, “socialism and communism were foreign words” to him and most other workers. At his association in Leipzig, there are lessons given in English, French, bookkeeping, and political lectures – Bebel himself participated in the bookkeeping and stenography lessons. On Good Friday 1862, Vahlteich and Fritzsche presented a motion to make this association purely political. They were resoundingly defeated.

In the intervening years, Bebel read Lassalle’s writings and became more steadfast in his opposition to the ADAV’s outlook. When Wilhelm Liebknecht arrived in Leipzig in 1865, the pair struck up a fast friendship, often going on agitational tours together. In 1867, after receiving a prison sentence, August Bebel finally had the time to read the first volume of Capital. Liebknecht and Bebel wanted to chart a new course for the German workers’ movement: one that broke the tyranny of Schweitzer, and united all social democratic workers under one banner.

They sought to do this in two ways: through giving the existing network of workers’ educational associations a political direction, and through setting up the Sächsische Volkspartei (Saxon People’s Party) in August 1866. This was not a socialist party, nor was it a workers’ one, even if it appealed primarily to the workers within workers’ educational associations. Its programme focused on establishing a democratic Germany, in opposition to a Germany dominated by Prussia. It was a radically democratic programme: calling for universal, secret suffrage, a militia instead of a standing army, and for parliament to handle questions of war and peace – a demand that has yet to be met today. It consciously set itself apart from the ADAV on the question of Prussia. Some members of the ADAV attended the founding congress, including Friedrich Fritzsche – although ADAV members were instructed to keep their distance. The ADAV in the meantime experienced a split: prompted by Schweitzer’s decision to drop the emphasis on universal suffrage after 1867 and his sidelining of Countess Hatzfeldt, who regarded herself as the heir to Lassalle’s work. She and her supporters formed the Lassallean General German Workers’ Association (LADAV) in 1867.

All these parties competed in the North German Reichstag elections in 1867: with the result that the Sächsiche Volkspartei won four seats, the ADAV three, and the LADAV two. Bebel was distinctly unimpressed with one of the LADAV deputies, Mendes, whom he reported was “a dunce” who “did not dare speak without a morphine injection.” Although each of these groupings pledged non-cooperation with Bismarck, there was no love lost between them. Schweitzer and Liebknecht publicly clashed in the Reichstag over compulsory military service. Schweitzer accused Liebknecht of seeking to destroy the North German Federation, in tandem with “dispossessed princes and envious foreigners”. Liebknecht replied that Schweitzer had done him a favour, as he wanted an opportunity to make it clear that he had “nothing to do with the doppelgänger of Wagener”, that is, one of Bismarck’s closest counsels. He couldn’t resist presenting this to Engels as “Yesterday I killed Schweitzer.”

Simultaneously, both the ADAV and what became the Eisenachers attempted to court the favour of Marx and by extension, the International. Schweitzer sought to publish extracts from Capital in the Social-Demokrat and reopened correspondence with Marx in the Spring of 1868, pledging to honour him at his organisation’s forthcoming congress. Meanwhile, in a letter to Engels in January 1868, Liebknecht insisted he had done everything he could for promoting Capital, including printing the preface in multiple papers, mentioning it dozens of times in his correspondence with “influential” people and bombarding the Austrian press.

However, although Marx and Engels were undoubtedly closer to Liebknecht than to Schweitzer, they weren’t impressed with either. When Marx wrote to Engels in 1870 to praise his preface of The Peasant War in Germany, he commended the “the double thrust at Wilhelm with the People’s Party and Schweitzer with his bodyguard of ruffians.” Liebknecht and Bebel, in seeking to distinguish themselves from Schweitzer’s closeness to the Prussian state, still saw cross-class alliances to achieve democratic demands as fruitful. But this would change.

In 1868, Bebel was the chair of the originally liberal Verband der Deutscher Arbeitervereine, which had undergone a steady process of politicisation. At the 1868 Nuremberg Congress, Bebel and Liebknecht sensed the opportunity to make this association adopt a radical programme – one that all but made it into the foundation for a workers’ political party. Here 115 delegates, representing 93 local associations, voted on a motion that declared: “The emancipation of the working classes must be the work of these classes themselves. The struggle for the emancipation of the working classes is not a struggle for class privileges and monopolies, but for equal rights and equal duties, and for the abolition of all class rule” and affiliated them to the International Workingmen’s Association. Despite the attempt of the organisation’s right wing to remove the discussion from the agenda altogether, 69 delegates voted for the motion. When it was accepted, the 41 who voted against left the room. By splitting the Verband, Bebel and Liebknecht created a working-class based internationalist political organisation.

It’s worth dwelling on what is meant by internationalist here – as the organisation did not stop at making a rhetorical expression of solidarity with workers in other countries. The Congress discussed the issue of armaments, and unanimously adopted a motion, proposed by Liebknecht, stating that:

In that it further gives princes the power to pursue wars against the will and wishes of their people, and moreover to disregard the will of the people, the standing army is the source of a persistent threat of war, and the means of dynastic wars of conquest abroad and the suppression of rights and freedoms at home.

The congress hence recommended its members should only vote for Landtag and Reichstag deputies who would never vote for government bills that give a penny to the maintenance of the army. Antimilitarism was less contentious at this stage than the question of land.

Just under a year later, in August 1969, this formation of workers’ associations became the basis for the Eisenach Congress, which formally established the Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands. It is worth noting that Bebel was opposed to “Arbeiter” (or workers’) being in the name, but he accepted the outcome of the democratic vote . He also wanted the party to be “democratic socialist” rather than “social democratic” – in a move reminiscent of the interminable debates about names today. This Congress was not only attended by ‘Eisenachers’, roughly one third of the attendees were members of the ADAV under Schweitzer, although they, after a struggle that came very close to violence, were excluded from holding voting rights. The evening that the delegates’ mandates were due to be validated, the Eisenachers gathered in a pub called the Golden Lion, while the ADAV assembled in The Ship. Bebel had heard reports that the ADAV (whom he refers to as ‘Schweitzerians’ in his memoirs) intended to disrupt the proceedings by force. Two emissaries of the Eisenachers were elected to request those in The Ship exchange their mandate cards for red identification cards, while the stairs of the Golden Lion were occupied by the strongest of the Eisenachers. In Bebel’s recollection, these members faced down roughly one hundred ADAV members, until the proceedings were adjourned and recommenced the following day.

The Eisenach programme was not substantially different from the Nuremberg programme adopted by the VDAV in 1868; this explains the relative ease the VDAV had in dissolving into the SDAP. It too coupled radical democratic demands, such as universal suffrage for men over twenty, with socialistic ones such as “the abolition of the present mode of production (the wage system)”. But how they imagined this would be done demonstrated the influence of Lassallean political economy, calling for the “the full proceeds of labour” to be obtained for every worker through “co-operative labour”. Marx would spill much ink in 1875 attacking the phrase “proceeds of labour” as an unclear and ambiguous Lassallean keyword. At this point, however, the Eisenachers had consolidated themselves into a democratic organisation, committed to agitating and propagandising for a democratic state and the emancipation of the working class. It also rivalled the size of the Lassallean ADAV, even if its strength was distributed unevenly.

The ADAV and the SDAP Go Head to Head

Germany now had two Social Democratic parties with parliamentary representation. And they both hated each other. On 22 September 1869, Liebknecht’s paper, the Demokratische Wochenblatt published a scathing open letter addressed to Schweitzer, shortly after he had been released from prison, accusing him of “seeking, through the most disgraceful means, absolute domination over German workers” and “deliberately stoking division among socialist workers”. So the road to unification would be a rocky one indeed.

The existing split was aggravated in 1870, by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. In a conflict sparked by succession to the Spanish throne, nearly 200,000 would die. Napoleon III had declared the war. In the German states, by the bourgeoisie and workers alike, it seemed like Germany was fighting a defensive war. Even Marx’s first address to the International Workingmen’s Association in London, in the summer of 1870, points to the war’s ‘defensive character’. But Bebel and Liebknecht, motivated more by anti-Prussianism than antimilitarism, took a different view. When it came to the North German Reichstag voting for war credits, they abstained. They were denounced by the Braunschweig Committee of their own party, who saw the war as a defensive one. The ADAV Reichstag deputies voted for war credits.

But the wave of war fever would not last too long. After the Battle of Sedan, when Napoleon III was captured, all illusions about the war waged by Bismarck were dispelled. It was clearly a war of annexation. In November 1870, all Social Democratic deputies voted against war credits. And shortly before Christmas, on 17 December 1870, Bebel and Liebknecht were imprisoned on charges of high treason, in part because of their statements against the war, and remained in solitary confinement.

The war also put the organised workers’ movement on the backfoot. Many working men had not yet returned from the war when elections were declared. In March 1871, in the first elections of the Reichstag of the unified German Empire, only Bebel was successfully elected. He was elected in part due to the rank-and-file of the ADAV disobeying their organisation’s line on run-off elections. The ADAV’s policy was to abstain in run-off elections between “reactionaries” and the SDAP, and to vote for liberals against the SDAP. As Bebel recounts, the Leipzig members of the ADAV had “too much of a sense of honour and class consciousness” to follow such instructions. Similar scenes played out in other German cities, where ADAV candidates refused to sign declarations endorsing their own organisation’s tactic for run-off elections.

Schweitzer was clearly losing his grip over the party. In the wake of his electoral defeat in the Reichstag elections, Schweitzer stood down from the leadership of the ADAV on 24 March 1871, claiming that he could no longer make the sacrifices required. It seemed much more likely that he realised his dictatorship was no longer tenable: he could no longer afford to fund Der Social-Demokrat, for one, especially given its subscribers had fallen to 2,700.1 Such were his finances (and his entitlement to party funds) that upon standing down as president, he convinced the ADAV to take over 1,500 Thalers of his personal debts.2 With Wilhelm Hasenclever being elected to the presidency, the ADAV would take on a new political orientation. At their next congress in May 1872, hot on the heels of strike waves involving thousands of workers in Hamburg and Berlin, the congress decided to dissolve the ADAV unions and fold themselves into broader union organisations.

The Turn Towards Unification

While the ADAV enjoyed a new lease of life, Bebel and Liebknecht were awaiting a trial for high treason, which finally took place in March 1872. It was an unusually long and highly publicised trial. To make the charge of “high treason” hold up, the prosecution chose to put Marxism on trial: producing the Communist Manifesto as legal evidence. Many of Liebknecht’s and Bebel’s writings were scrutinised for revolutionary intent, and they were also questioned on their choice to reprint poetry from the 1848 revolutionary period, by Freiligrath and Herwegh. It was quite obviously a stitch-up. And hence a fantastic propaganda opportunity. When they were sentenced to two years each in prison, they went out to drink a bottle of wine at Goethe’s favourite student tavern, immortalised in Faust, Auerbach’s Cellar.

The trial transformed them into cause celebres for the workers’ movement. In July, Bebel would be sentenced to a further nine months in prison, charged with lèse-majesté. These prison sentences did not deal a disastrous blow to the leadership of the SDAP, due to its impressive organisational structure. The administration of the party was divided between an executive committee, a control commission and, as the final authority, party congress, all located in different places. Such a structure had been constructed precisely to avoid replicating the concentration of power in the hands of the president, as had happened in the ADAV.

Consequently, in September 1872, while Bebel and Liebknecht languished in prison, the party congress in Mainz debated efforts to cooperate and even unify with the ADAV. The motions passed obligated both the executive committee and local branches to work towards combining forces with the ADAV wherever possible. Revealingly, delegates also stipulated that the SDAP’s paper, the Volksstaat, desist from polemics against the ADAV and its leaders, and to respond to provocations with silence, unless the executive committee deemed a reply necessary.

This would prove more difficult in practice. The ADAV rebuffed the efforts made in Berlin for unification of the two wings of the socialist workers’ movement. In early October 1872, for instance, ADAV members flooded a public meeting of the SDAP and passed a resolution declaring “the assembly is in complete agreement with the principles and organisation of Lassalle.” Many public SDAP assemblies in Berlin suffered similar wrecking, and pushed the SDAP into ever smaller pubs, up until 1873.3 The frustrations of dealing with sectarian clashes on the ground, combined with the ADAV’s official policy against unification, undoubtedly contributed the SDAP voting to discontinue unification efforts in August 1873.

However, the ADAV’s attitude would be forced to change: state repression blunted sectarianism’s edge. In Bebel’s recollection, the appointment of Tessendorf to the Berlin city court unleashed an unprecedented wave of prosecutions, and heavier sentences than socialists had ever seen before. In Prussia as a whole, in 1874, 87 Lassalleans, including some of their best organisers, were sentenced to 211 months and 3 weeks in prison, in 104 trials. A similar situation unfolded in Saxony, where the SDAP bore the brunt of the persecution. Through the strict enforcement of the association laws by the police, the ADAV was being pushed to the brink of dissolution.

On 11 October 1874, Bebel received a letter from Liebknecht – both still serving out their prison sentences. Liebknecht informed him that a significant portion of the ADAV leadership now wanted unification; they were even disappointed to hear that Liebknecht was unwilling to rush ahead with a unification congress the very next month. Both the ADAV and SDAP leadership entered discussions preparing the ground for the unification of Social Democracy.

In the New Year, the discussions were shared with the members of both parties. Writing to the membership of the ADAV in the Neuer Social-Demokrat, Wilhelm Hasenclever stated that the majority wanted unification, but wanted Lassalle’s outlook and demands to be preserved in the programme, and were in favour of a centralised organisation. The discussion in the party press was coupled with joint meetings on the ground: the Volksstaat reported, for instance, a meeting in Verden, Saxony that covered the history of the German workers’ movement since 1848, charting the emergence of both wings of Social Democracy.

By the beginning of March, a draft programme had been prepared by a commission of 16 ADAV and SDAP leaders. When Bebel received it on 5 March, while still in prison, he was infuriated, especially as Liebknecht told him there was nothing more to be achieved. Bebel himself only received it two days before it was printed. Engels, who had similarly been kept in the dark by Liebknecht on the progress of the negotiations, wrote Bebel a sharp letter warning him that the presence of various Lassallean stock phrases meant that both him and Marx would be forced to disavow any new party. But this draft was not the final word. Members of both organisations participated in meetings from the moment the draft was printed, criticising unclear definitions (what was meant by ‘direct legislation by the people’?) and the fine details of organisational structure. There were heated debates reported, where mass meetings passed motions around whether “decisions about war and peace” should be resolved by the “people’s representatives” or “the people”.

The delegates who attended the Gotha Congress in May had hence undergone several months’ of political education; they were well-versed in the dots and commas of the programme draft, and they were prepared to fight it out. 127 delegates represented nearly 26,000 members, with the ADAV counting 71 delegates and the SDAP, 56. An atmosphere of distrust lingered – Friedrich Fritzsche took the floor to complain that the SDAP chair Ignaz Auer described the Eisenachers as “poor but honest”, suggesting, he argued, dishonesty on the part of the ADAV.

But the substantial debate was political – with motions discussed concerning virtually every point of the programme. The “undiminished proceeds of labour” that so upset Marx as point 1 became “the collective product of labour”. The “right of coalition” became “the unrestricted right of coalition”. Instead of speaking of the tasks it had in “common with workers of all civilised countries”, it speaks of being prepared “to fulfil all duties placed upon workers to make the brotherhood of human beings a reality”.

On 27 May 1875, twelve years after Lassalle founded Germany’s first workers’ party, the work of unification was complete. Workers closed out the festivities by singing the Workers’ Marseillaise. A politically heterogeneous, but genuinely revolutionary socialist workers’ party had been founded: unified by clear demands, for the first time on secure financial footing, and ready to weather state repression. And it was not handed down from on high by a chosen few who had all the answers figured out. It was created by workers organising themselves, from root and branch upwards, to determine and achieve their aims.

The Gotha Programme was not a perfect programme, by any means. But it reflected the work of not just a handful of leaders, negotiating behind the scenes, but the consciousness and practical commitments of thousands of workers in Germany: the result of a decade of organised socialist activity. It created a structure by which vital political questions could be debated, perspectives could be clarified and new strategies could be formulated.

In a way Engels was right – it was an “educational experiment”. It lasted until 1914. In it, generations of socialists were trained to think about the world, to act to change it, to hold onto hope in the direst of circumstances. If we could get to something like it today, we’d have much to be proud of.

- Mehring, Geschichte der Deutsche Sozialdemokratie v. 4 (1913), p. 17 ↩︎

- Tölcke, Zweck, Mittel und Organisation des Allgemeinen deutschen Arbeiter-Vereins : ein Leitfaden für die Agitatoren, Bevollmächtigten und Mitglieder des Vereins, p. 82 ↩︎

- Bernstein, Geschichte der Berliner Arbeiterbewegung vol.1 (1907), pp. 247-250 ↩︎